FOELSCHE, Paul

- pixeltoprint

- Jul 11, 2021

- 15 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2021

Born - 30 March 1831, Moorburg, Hamburg, Germany

Paul Heinrich Matthias Foelsche was born in Moorburg, Hamburg in Germany on 30 March 1831. Because that region’s records were destroyed in the Second World War, little information remains about his early life. Born into a middle class family, he served in a Hussar regiment from the age of 18. He was a soldier for no more than five years, immigrating to South Australia in 1854. In 1856, he joined the South Australian Police but, unfortunately, because his service record does not reveal his previous occupation, we do not know what work he undertook in the intervening two years.

First posted to Strathalbyn in the south-east of South Australia, Foelsche rose through the ranks from trooper third class to trooper first class relatively quickly, reaching that rank in March 1860. This was a curious year for Foelsche. He was one of a number of police who through no fault of their own were either reduced in rank or had their services terminated due to budgetary constraints. Reduced to second class trooper in July, Foelsche regained the first class rank in August. He went on to become a corporal in 1867 but once again, due to Government constraints, in February 1869 he was reduced to the rank of lance corporal.

Paul Foelsche was an early pioneer in photography in the NT and the images that he took are a remarkable record of the early Territory.

Finally, in December 1869, he became sub–inspector in command of Police in the Northern Territory. It is noteworthy that he was naturalised on 6 December 1869, which suggests that he was required to become a British citizen in order to obtain the position. Whilst at Strathalbyn, Foelsche married a local woman, Charlotte Georgina Smith, and they had two daughters Mary and Emma. He also used his time in Strathalbyn to acquire skills as a dentist, photographer and lawyer. These skills were to prove useful to him in the Northern Territory, in particular photography. Some of his photographs remain as an important historical record. These photographs were exhibited at the aris Exhibition in 1878 that brought the Northern Territory to the world’s attention. He acquired skills as a gunsmith, becoming an expert at making ‘gunsights and gunstocks, also in colouring rifle and gun barrels.’ He became active in Freemasonry during his time at Strathalbyn, joining the organisation in 1861. He became the first Senior Warden of the Lodge of St. John at Strathalbyn in November 1868 and in June 1869 became the Lodge’s Master. Foelsche was a strange choice to lead the contingent to the Northern Territory. Whatever his skills and abilities, and they were many, he lacked experience of leadership at senior rank and it is difficult to understand why a sergeant or sergeant major was not promoted to the position. There is some evidence to suggest that the Northern Territory was not a popular posting because a sergeant major apparently declined to apply for the position despite being encouraged to do so. Nevertheless, there were many members senior to Foelsche suitable for appointment. A Freemason historian, Jack Haydon, has suggested another reason for Foelsche’s selection:

The fact that only 14 months elapsed from Foelsche’s entry into the craft whilst still a trooper, to his arrival in Palmerston as a Past Master and Sub-Inspector in charge of Police, implies that more than mere coincidence was involved and although I have no proof, I see the hand of his superior officers and other Leaders of the Community, by whom he was held in very high regard in this sequence of events.

Haydon’s interpretation does appear plausible, Foelsche was also popular with the civic leaders in Strathalbyn. On the eve of his departure for Darwin, a dinner was given in his honour attended by about ‘50 gentlemen, comprising most of the leading inhabitants of the district’. The chairman, in proposing a toast to Foelsche, said that he realised what a considerable promotion it was for Foelsche. He continued by saying that the diners were all sorry to see Foelsche go as he had gained universal respect for his kindness, tact and ability. Could the Freemasons have been involved in Foelsche’s promotion? It is not possible to answer this question with certainty, but suspicion must remain. Freemasonry is: One of the world's oldest fraternal societies. It is made up of men who are concerned with moral and spiritual values and who pursue a way of life that complements their religious, family and community affiliations. They seek a better way of life and treat all men as equal regardless of race, religion or social standing. Freemasonry was also sectarian, although there is some debate about whether this is true now. In Foelsche’s time, Roman Catholics were not permitted to join because Freemasonry was considered incompatible with the Catholic faith. The Lodges therefore, comprised small groups of well connected, Protestant men. To suggest that they would not aid one another in their professional lives if the opportunity arose is unbelievable. Foelsche wrote to his friend John Lewis in 1877, asking that Lewis use his influence with Sir Samuel Way, the Chief Justice of South Australia and a fellow Freemason, to have him appointed as a visiting justice at the Darwin gaol, a position he gained. There have been other allegations over the years that Freemasonry has influenced Australian policing and Freemasonry has long influenced British policing. The belief became so widespread in Britain in 1997 that the House of Commons enquired into the penetration of Freemasonry in the police and judiciary. No evidence was found to substantiate the allegation that the Freemason activity was widespread within the police, magistracy or legal profession; however, the fact that such an enquiry was necessary indicates strength of suspicions that were held. Freemasons might now be less overt in Britain but the small size of South Australia’s population in 1869, and the positions held by many of the Freemasons, renders it highly likely that his brother Masons helped Foelsche. The influence of The presence of Oddfellows at the dinner is also important. Like the Freemasons, the Grand United Order of Oddfellows was established to provide mutual aid to its members. Lodges were established in Sydney in the early 1840s and gradually spread to the other colonies. The presence of Oddfellows at the testimonial dinner suggests that the Lodge members wished to honour his work in Strathalbyn. It is also possible that Oddfellows, as well Freemasons, assisted his career. Several influential people held Foelsche in high regard. For example, he was friendly with G.L. Reed, who went on to become Secretary of the Police Department. It might thus be that his promotion was not due so much to the Freemasons as his friendship with many influential people more generally. Such a suggestion overlooks the fact that most of his influential friends had come to know him through his Freemasonry. On the available evidence it seems that after Foelsche arrived in Strathalbyn and became a senior figure in the South Australian Freemasonry, his career blossomed. His selection to lead the Northern Territory contingent of police is difficult to explain when many more senior members were overlooked. His ability as a police officer is not questioned, but his lack of seniority suggests that he should not have been awarded the position. Although it is not possible to conclusively state that Foelsche’s Freemason or Oddfellow connections were responsible for his gaining the appointment, it does seem that Haydon was correct. More than mere coincidence was involved in his appointment. Foelsche was undoubtedly an able police officer. At Strathalbyn, he had often been selected to undertake difficult tasks where tact and discretion were called for. After he arrived in the Northern Territory, he continued to undertake some operational tasks as well as administering his small detachment. Never one to sit in the office, he became personally involved in many of the more serious events during the time that he commanded the force. His obituary recorded the fact that he ‘frequently undertook the investigation of cases of murder by the blacks’. Foelsche did not travel extensively in the Northern Territory but he visited all the police camps at which his members were stationed. He undertook a notable journey in December 1873 when he inspected the camps on the goldfields and made enquiries about reports of assaults amongst the Woolwonga tribe near Daly River. His detailed report was indicative of an experienced police officer, as it detailed the enquiries he undertook and then in a clear, concise manner provided a wealth of information for the Government Resident and a included number of recommendations.............* .........When Foelsche arrived in the Northern Territory he lacked experience as a leader. This was to be the cause of problems for him during the early years of his service in the Northern Territory. Foelsche arrived in Darwin in January 1870 and he immediately faced a disciplinary problem. Captain Smith of the schooner Gulnare reported troopers Boord and Smith for misbehaviour on the journey from Adelaide. The complaint was based on threats uttered by the two troopers over the quality of food served to the ships passengers. Foelsche immediately suspended the two and returned them to Adelaide. In retrospect, the penalty was harsh, probably deliberately so in order to demonstrate that Foelsche would tolerate no breaches of discipline. Interestingly, he was far more lenient when he faced a mutiny by some of his men in mid 1870. When the troopers refused to participate in the building of police premises, he gave them a week off duty to consider the situation. Such a low-key response is contrary to Foelsche’s normal actions when faced by a disciplinary problem. It appears that he sympathised with his men. In writing to the Commissioner later about the refusal of his men to help in the building project, he noted that breaches of discipline and symptoms of insubordination had appeared. He cited a lack of special regulations as the reason why the troopers had not been disciplined for their refusal to work. The Commissioner responded by observing tartly that: The rules and regulations for preserving discipline are very simple – viz., the strict obedience to orders and I do not know how any express rules can be framed for the Northern Territory that do not exist in Adelaide or elsewhere. It is inconceivable that Foelsche was not aware of the full range of his powers; after all, he had used them previously. A more likely explanation is that he agreed with his troopers that carpentry was not a police occupation and thus did not act firmly against the mutineers. Foelsche faced another significant rebuff in the later cases of Constables Smith and Hill. He dismissed Smith from the police force for seeking to gain favourable reports from a reporter by plying the scribe with free liquor. Hill was suspended in 1884 for an unknown offence. He was also dismissed from the police force for leaving the barracks whilst under suspension. The two constables petitioned the South Australian House of Assembly for an inquiry into both dismissals and the management of the police force. Samuel Beddome, an Adelaide Magistrate, investigated the removal of the two members. Beddome, reporting to the House of Assembly, wrote that ‘in neither case do I find sufficient grounds for so extremely harsh a step as dismissal, and I consider both entitled to compensation’. While no general enquiry was held into the dismissals, Foelsche had acted unduly harshly yet again. He was sensitive to his official position, and during the first half of his service in the Northern Territory, argued with many individuals and bore grudges against them for lengthy periods. The first disagreement occurred between Foelsche and Captain Bloomfield Douglas, the Government Resident. Foelsche initially impressed Douglas who was not popular either with the general population or amongst the police. When he sought permission for his family to join him in August 1870, Douglas wrote to the Minister that ‘Mr Foelsche by his co-operation gives me great satisfaction’. In September 1870 Douglas advised the Minister that, ‘The Police under Sub-Inspector Foelsche continue to give me good satisfaction’. By 1871, however, matters had changed. Douglas and Foelsche had fallen out over the command of the police force and because Foelsche had written direct to the Commissioner. Douglas complained to the Minister that, ‘Mr Foelsche has doubtless been a good policeman but he is perfectly unfit for the position he now holds.’ Commissioner Hamilton disagreed. In Hamilton’s view, Foelsche had ‘made one or two mistakes with reference to his position but I am not quite sure that he has not been subjected to treatment by the Government Resident which has harassed and annoyed him’. Foelsche remained in his post. It appears likely that the clash between Douglas and Foelsche arose from the latter’s refusal to permit the police to help in building the police station and quarters. Douglas considered that the police had insufficient work; indeed, he considered that they had been ‘for months lounging around unemployed’. Although Douglas considered it would be healthy for the police to help in the building of their quarters, Foelsche disagreed. After the police officers refused to build a police station, Douglas complained that Foelsche did not appear willing for his men to engage in active, arduous duties. His next quarrel was with J. Squire, the Manager of the British Australia Telegraph Company, over Squire’s employees selling liquor without a licence. Foelsche charged the offenders and, in a letter to the South Australian Commissioner of Police, criticised Squire for failing to stop the practice and for then interfering in the case when it came to Court. Squire was the Government Resident’s son-in-law. When Foelsche’s letter reached Adelaide, a copy was sent to Darwin and Squire was invited to comment. Squire clearly considered Foelsche to be of a lower class and subordinate to himself, ‘The sub-inspector displays an incredible amount of impertinence — He ignores those in authority over him…and proved himself to be a most dangerous man…he [should] be called upon to make an unqualified apology’. As the Commissioner and Minister sided with Squire, Foelsche was ordered to make an apology. In this instance Foelsche was unfortunate; he had merely done his duty and reported the facts of a breach of the Licensed Victuallers Act and Squire’s part in the affair. He was reprimanded because he had reported on those closely linked to the administration’s hierarchy. This case demonstrates the power held by those in dominant positions in the small Northern Territory community. Foelsche’s next disagreement was with his second in command, Corporal Frederick Drought. He had initially reported favourably upon Drought, writing to the Commissioner in June 1870 that ‘It is due to Corporal Drought to state that he has rendered me every assistance to uphold the character of the South Australian mounted police’. In May 1873, the relationship changed when Corporal Drought and Trooper Jones argued over the ownership of a pair of horse hobbles. A brawl developed and Drought charged Jones with assault but did not tell Foelsche he had done so. Foelsche took issue with Drought and recommended to the Commissioner for Crown Lands (and the Northern Territory), Thomas Reynolds, the dismissal from the force of Drought. Reynolds concurred but also dismissed Jones because he had been dealing in mining ventures whilst still a police officer. Foelsche argued that Jones was a good and zealous officer and should be permitted to stay in the force. Reynolds disagreed and Jones employment was terminated. Other members then became involved in the affair and Foelsche sought to bolster his position. He now alleged that Drought had attempted to turn young members of the service against him and generally disrupt the force. The most serious allegation, in Foelsche’s eyes, was that Drought had referred to him as either a ‘damned German’ or a ‘German bastard’. He had formed the opinion that Drought was not only insubordinate but also sought to undermine his authority in order that he, Drought, could be promoted in his place. The evidence does not support such views but suggests that Foelsche’s inexperience and sense of dignity blew the issue out of proportion. Indeed, the Commissioner was later to write that there was insufficient evidence on which Drought should have been dismissed and that Foelsche should have refrained from accepting the ‘tattle’ about himself. His next major disagreement was with Sergeant Badman. In September 1873, Foelsche had been obliged to resign his office as Keeper of the Gaol when Badman was appointed to that position. The reduction in his powers apparently rankled Foelsche because he directed Badman how to run the gaol. Badman refused to accept Foelsche’s instructions, believing that he alone was responsible for the operation of the gaol. The argument led to ‘a slight unpleasantness’. The dispute raged for over two years with Foelsche reporting in 1876 that Badman’s ‘conduct… was anything but a subordinate towards a superior’. Foelsche in a display of petty tyranny, delayed payment of Badman’s ration money until long after other members received their allowances. Badman alone could not afford to bring his family to Darwin and sought some compensation to enable him to do so. Foelsche refused this support. Eventually Badman resigned and returned to Adelaide. Foelsche had allowed a personality conflict that he allowed to openly develop with Badman. Foelsche could also be abrasive to his friends. Writing to John Lewis in January 1877, Foelsche, angered by Lewis’s tardy response to previous correspondence, wrote, ‘when you have been married as long as I have perhaps you will be able to find time to answer a civil question’. This, whilst appearing jocular was not; in the context of the letter the remark was one of anger. At least one his members considered Foelsche to have a mean streak. For example, he threatened to make all the troopers suffer after Trooper Stretton gave an old pair of uniform trousers to an Indigenous male in November 1870. Foelsche was also irked by decisions taken by a range of government residents. In an undated letter, he told Lewis that the Government Resident had displayed ill feelings towards him again and tried to hound him out of his office and give it to the gaoler. He referred to the second Government Resident, Edward Price, as a ‘little two-faced man’. He also became concerned that Price intended to replace him as the senior police officer. This culminated with Foelsche asking Lewis to help him keep and improve his position. In 1913 he complained that Maurice Holtze had been unfairly demoted from his position as Government Secretary and Dr. Strangman had been persecuted. The words ‘insulted’, ‘unfair’ and ‘persecution’ suggest that Foelsche had strong views on many matters and was inclined to pursue them. Many of the cases cited above confirm the views expressed about Foelsche’s sensitivity to official dignity and meanness. They display too, his tendency to disagree with friends and close associates over matters of small consequence. The arguments between Foelsche and others, especially Douglas, Price and Lewis, say much of relationships in the small settlement clinging to the shores of the Arafura Sea. The tropical heat would have been oppressive to those more accustomed to South Australia’s climate. The small number of Europeans also meant that they lived and worked closely together, magnifying any perceived injustice. As in any closed community, arguments broke out and feuds festered over real or imagined slights. William Sowden, visiting the Northern Territory in 1882, summed up the situation when he said:

…keep alive the grand old practice of scandal-mongering, and it is just now in fine feather…You would hardly think that about fifty of the ‘society’ people could afford to run two factions, but they do, much to the embittering of the private lives of each.

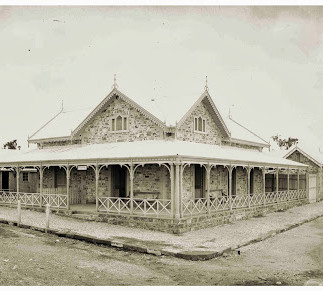

Based upon both his official and private correspondence, Foelsche was perhaps one of the most embittered of all the Europeans in Darwin. Initially living in a two-roomed tin hut, Foelsche later moved to a small, crude, two or three roomed house in Mitchell Street. He was a devoted family man and, in August 1870, sought to bring his family to Darwin. After his wife Charlotte and two daughters Mary and Emma arrived in Darwin, they made this house a bright and cheery place. He continued to use his skills as a dentist, photographer, lawyer and gunsmith in the small settlement. When not engaged on policing tasks, about which we know very little, Foelsche became an avid photographer. His photographs were displayed in exhibitions overseas to publicise the Northern Territory. He captured on film instances of police activities. At least one, the capture of Ah Kim in 1870, was a reconstruction but it still provides details of one of the major events in early police history. Click here to see more of his photo collection. Many of his photographs are displayed in police headquarters in Darwin as a vivid reminder of the early settlement of the Northern Territory. Foelsche also took an interest in the Aboriginal people of the Northern Territory. He gathered ethnological information and attempted to learn the local language. A paper prepared by Foelsche was read to the Royal Society in Adelaide in 1881. His interest in Aboriginal people should have helped the police better understand this segment of Northern Territory society but such was not the case. Foelsche had a Lutheran background and remained active in church affairs in the Northern Territory. Indeed, he became a member of the Parish Council of the Wesleyan Church and a trustee of Lot 639 on the corner of Knuckey and Mitchell Streets, on which the Church was built. His membership of the Wesleyan Church Council led him to yet another disagreement when, in 1899, he and six other members of the Council resigned, finding that they could not work harmoniously with the Minister, the Reverend S. Stephens. He also remained active in Freemasonry in Darwin. He finally sought to establish a Lodge of the Freemasons in Darwin by presenting a petition to the Grand Master ‘which was sponsored by the Master and petitioners of the Lodge of Friendship No. 1 on the register of the South Australian Constitution’.81 The petition was accepted and a meeting to form the new Lodge was held in the Victoria Hotel on 18 February 1896. Foelsche’s personal moral code resulted in him being the subject of public ridicule in 1881, when he and seven other leading Darwin residents cancelled their subscriptions to the Northern Territory Times and Gazette after that paper published an article on prostitution among the Aboriginal population. Foelsche, Doctor Morice, V.L. Solomon (soon to become a parliamentarian), D.W. Gott, J.T. Bull, S.S. Moncrieff, L. Webster and F. Becker became known as the ‘Octagonists’ and the subject of much merriment and banter among the non-Indigenous community for their blinkered view of life in the small community. He took 12 months leave from February 1903 and formally retired on 1 February 1904. He continued to live in Darwin after his retirement until his death from gangrene, arteriosclerosis and senility on 31 January 1914. His two daughters survived him.

* paragraph removed from main text due to potentially offensive content. Full text remains in the thesis for reference purposes.

Below are links to a presentation on Foelsche by the SA Police Museum.

South Australia Museum: Foelsche's Frontier Photography

Paul Heinrich Matthias Foelsche (Wikipedia page)

留言